E. Pauline Johnson (Karen Dearlove)

On a cold evening in January of 1892, before a packed house of 400 young Liberals in Toronto, a young woman stood on stage and recited by heart her dramatic poem, A Cry from an Indian Wife. Written from the perspective of a native woman, about the North-West Rebellion of 1885, the poem challenged the fervent nationalism of the recital’s audience with its clear enunciation of native rights and condemnation of western colonialism: “They but forget we Indians owned the land/ From ocean unto ocean; that they stand/ Upon a soil that centuries agone/ Was our sole kingdom and our right alone.” While her recital was enthusiastically greeted with applause, few in the audience realized that the poem’s author and performer was herself one of the First Nations people about whom she wrote. The performance marked the beginning of the astonishing career of Tekahionwake, also known as E. Pauline Johnson.

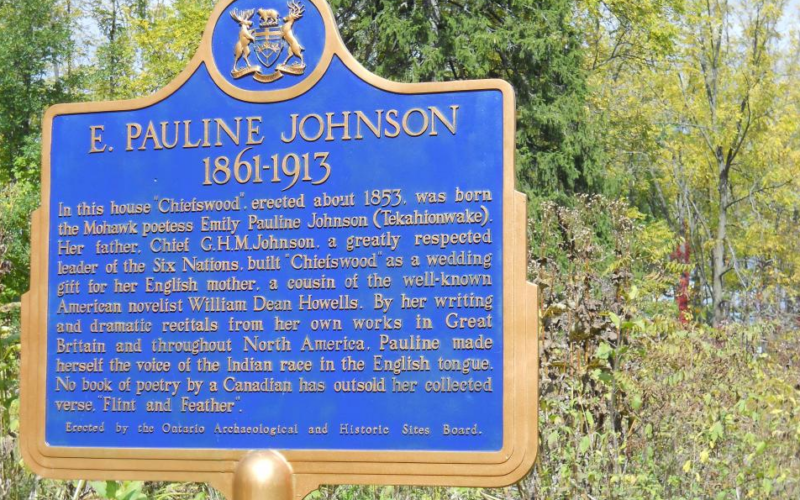

Born on the Six Nations’ reserve in 1861, E. Pauline Johnson was the youngest daughter of Mohawk Chief George H.M. Johnson and his English wife Emily Howells. George Johnson worked as an interpreter first for the Anglican missionary at the Six Nations and later for the Canadian government. George Johnson carried on the tradition established by his grandfather, George Martin, and father, John “Smoke” Johnson, acting as an intermediary between Native and European cultures. Chiefswood, the family’s home, built by George Johnson, became an important meeting place for people coming from outside of the reserve to the Six Nations, and physically represented the concept of cultural meeting in the home’s design of two identical front doors. Raised to appreciate both her Mohawk and English heritage, E. Pauline Johnson continued her family’s role as intermediaries in her poetry and stage performances.

Following her first performance in Toronto in 1892, E. Pauline Johnson’s career as a stage performer quickly took off. She travelled across Canada, the United States, and three times to England, reciting her poetry on-stage in dramatic fashion. Billed as the Mohawk Princess and Iroquois Indian Poet Reciter, E. Pauline Johnson adopted her great-grandfather’s name, Tekahionake, meaning double-life, as her stage name. In her performances E. Pauline Johnson expressed the double-life of her mixed Mohawk and English heritage through costume. For the first half of her performance she wore a buckskin outfit (bought through the Hudson’s Bay Company) that she adorned with rabbit skins, ermine furs, a bear claw necklace, feathers, wampum belts, and silver ornaments that once belonged to her great-grandmother. A mish-mash of popular Native imagery, E. Pauline Johnson’s performance outfit accentuated her native heritage for an audience that knew very little about First Nations peoples. In the second part of her performance she arrived on stage in elegant Victorian dress, her long dark hair stylishly pinned up, the picture of the prim and proper Victorian lady.

Yet in the late 1890s and early 1900s, E. Pauline Johnson’s very public career was considered anything but lady-like, as her activities challenged the acceptable norms for women, and for Native people. Never marrying or having children, she eked out a living supporting herself through her published writing and stage performances. Her constant travelling across Canada, the United States, and to England demonstrated an independence and sense of adventure which, at that time was generally frowned upon for women. Her choice of career as a stage performer was also criticized by many, including her own mother, as a vulgar profession for a woman. Lastly, E. Pauline Johnson brought First Nations’ issues and perceptions to the forefront in her writing and performances, at a time when recent events such as the North-West Rebellion were still fresh in the public’s consciousness and one-dimensional native stereotypes abounded. She countered these stereotypes in writings like the article, A Strong Race Opinion on the Indian Girl in Modern Fiction, which criticized the representation of Native women as fawn-like or submissive.

Besides her performances, E. Pauline Johnson published three volumes of poetry – White Wampum (1895), Canadian Born (1903), and Flint and Feather (1912). She also published a volume of native stories from the West Coast, Legends of Vancouver (1911), and various articles published in magazines. She retired from her stage career in 1909, settling in Vancouver, close to her beloved Stanley Park. While she intended to spend more time writing, E. Pauline Johnson was diagnosed with breast cancer and succumbed to the disease on March 7, 1913.

Her dying wish was to be buried in Stanley Park. Following a packed funeral procession through Vancouver on March 10, 1913, E. Pauline Johnson’s ashes were buried under a boulder in the park, in sight of Siwash Rock. In 1922, a monument to E. Pauline Johnson was unveiled at her burial site, which still stands today.

Despite her premature death, E. Pauline Johnson left a lasting impact and legacy on Canada and beyond. An international celebrity in her era, E. Pauline Johnson paved the way for future women and native writers and performers. Her legacy has been honoured in Canada through the naming of five schools, located in Vancouver, Brantford, Hamilton, Burlington and Scarborough. In 1958, the Province of Ontario dedicated a plaque to E. Pauline Johnson at her home Chiefswood. In 1961, the Government of Canada issued a postage stamp of her on the 100th anniversary of her birth. E. Pauline Johnson was the first Canadian author and first Canadian native person to appear on a Canadian stamp. She was designated a person of national historic significance by the Canadian government in 1983, and her birthplace and childhood home of Chiefswood was designated a National Historic Site in 1992.